Your smartphone can crash and restart. Your laptop can freeze. Your smart TV can glitch.

A drone? It crashes once, and that's not a software problem anymore — that's physics.

That's why firmware development for drones operates under completely different rules. We're talking microsecond-precise timing, processors with 64KB of RAM running life-critical algorithms, and security challenges where a single vulnerability could mean hijacking mid-flight.

We'll explore the key challenges: real-time constraints, hardware limitations, fault tolerance, security threats, regulatory compliance, and testing strategies that keep these systems reliable.

Role of Firmware and Embedded Software in Drone Systems

Firmware in drone systems and embedded software aren't the same thing. Firmware sits closer to the hardware — permanent software controlling basic operations like motor speeds and sensor readings. Embedded software handles higher-level logic: navigation, communication, decision-making.

Together, they're the brain and nervous system of your UAV. Why is this mission-critical? Because unlike your smartphone app that can freeze and restart, drone software doesn't get second chances. That's why embedded software development challenges in this field are so intense — there's zero room for error.

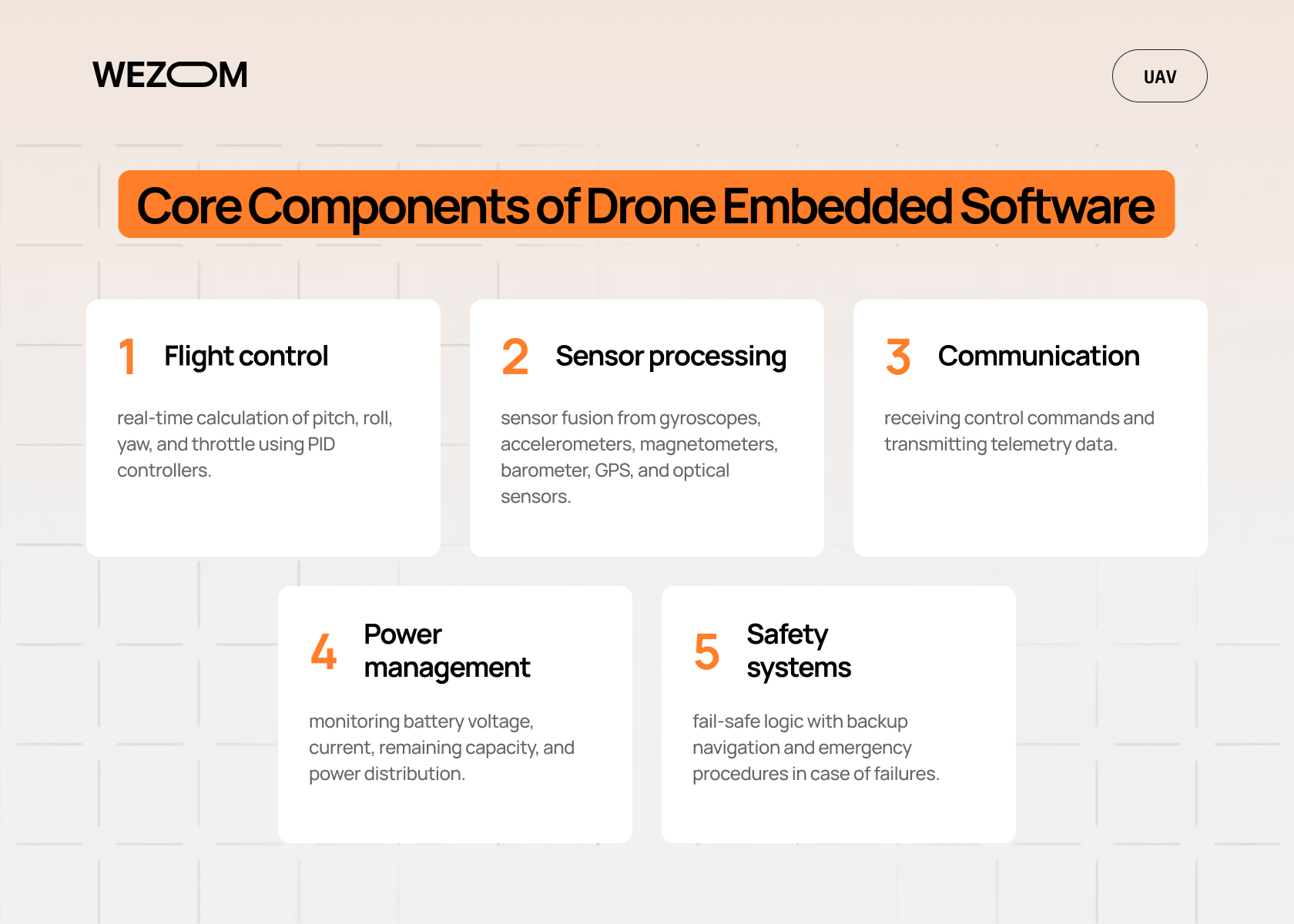

Core Components of Drone Embedded Software

Drone flight control software calculates pitch, roll, yaw, and throttle adjustments hundreds of times per second. PID controllers run these calculations continuously. Sensor data processing fuses inputs from gyroscopes, accelerometers, magnetometers, barometers, GPS receivers, and optical sensors — each feeding data at different rates.

Communication modules transmit critical flight data and receive control commands. Power and battery management tracks voltage, current draw, and remaining capacity while optimizing distribution. Safety and fail-safe logic kicks in when things go wrong — lost GPS triggers optical navigation, motor failure activates emergency protocols.

Real-Time Performance and Latency Constraints

Drone firmware typically runs on a Real-Time Operating System (RTOS). Not Linux, not Windows, those are way too unpredictable. An RTOS guarantees that critical tasks execute within specific time windows. We're talking microseconds here.

Latency is the enemy. Modern flight control systems like Betaflight operate with PID loop frequencies of 4-8 kHz, achieving response times as low as 2-5 milliseconds — critical for maintaining stability in challenging flight conditions. Achieving this precision represents one of the core challenges of embedded system development — juggling multiple tasks with different priorities, all competing for limited processor time.

Hardware Constraints and Resource Optimization

We're typically working with ARM Cortex-M series chips — 32-bit processors with limited clock speeds, constrained memory, and minimal storage. Powerful processors drain batteries and add weight.

| Resource | Typical Constraint | Developer Impact |

|---|---|---|

| CPU Power | 48-168 MHz clock speed | Algorithm optimization is mandatory, not optional |

| RAM | 64-256 KB typical | Careful memory management, no memory leaks allowed |

| Flash Storage | 512 KB - 2 MB | Compact code, minimal logging, efficient data structures |

| Power Budget | Every milliwatt counts | Aggressive power optimization, sleep modes, selective sensor polling |

The constant trade-off between performance and energy efficiency defines embedded software for drones. Want better navigation? That AI algorithm will drain your battery faster. Every feature request becomes a negotiation between what's technically possible and what's practically sustainable.

Firmware Reliability and Fault Tolerance

Sensors fail. It's not a question of if, but when.

GPS signal drops near buildings. Magnetometers get confused by electromagnetic interference. Optical sensors struggle in rain. That's where redundancy and fault tolerance come in — professional drones use dual or triple redundant systems for critical sensors.

Crash prevention strategies go deeper: geofencing prevents drones from entering restricted zones, automatic return-to-home kicks in when battery hits critical levels, and emergency landing protocols activate when multiple systems fail. The firmware constantly monitors altitude, battery voltage, signal strength, and motor performance — ready to intervene before catastrophic failure.

Security Challenges in Drone Firmware

Then there's security. Firmware vulnerabilities in consumer drones remain a persistent concern, with cybersecurity researchers consistently identifying critical weaknesses that could allow unauthorized access or control hijacking. The risks include: insecure boot processes, unencrypted communication channels, unauthenticated firmware updates, and GPS spoofing.

But here's the catch: security measures consume processing power and memory. Every encryption operation takes time. How much security can you implement without compromising real-time performance?

Firmware Updates and Lifecycle Management

Over-the-air (OTA) firmware updates are essential but terrifying. You're asking a flying device to replace its own brain. The process needs to verify authenticity, ensure sufficient battery power, maintain backup versions, and implement rollback mechanisms if updates fail.

Version control becomes critical when managing firmware across different drone models and hardware revisions. Backward compatibility means newer firmware must work with older sensors and components. And rollback strategies aren't optional: if an update causes unexpected behavior, the firmware needs to automatically revert to the previous stable version without human intervention.

Regulatory and Safety Compliance

FAA regulations mandate geo-fencing to prevent flights near airports, automatic altitude limits, and return-to-home functionality. EASA rules require remote identification — drones must broadcast location and operator information in real-time.

For commercial drones, software certification requires formal documentation: traceability matrices linking requirements to code, verification reports, and hazard analysis.

Logging and traceability are mandated. Firmware must create immutable records of flight data — GPS coordinates, altitude, battery status, control inputs, system errors. The challenge? Logging comprehensive data on devices with limited flash storage.

Testing, Debugging, and Validation

Testing embedded system development for drones involves software-in-the-loop (SIL) simulation, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing, and real-world flight testing. Debugging embedded firmware is its own special kind of pain — you can't just attach a traditional debugger to a flying device.

That's where automated testing for firmware becomes invaluable. Continuous integration pipelines run unit tests on every code commit, integration tests verify module interactions, and regression tests ensure new features don't break existing functionality. Automated tests can simulate thousands of failure scenarios, catching edge cases that manual testing would miss.

Best Practices for Overcoming Firmware Challenges

After years of working through challenges and issues in embedded software development, we've learned that modular architecture is non-negotiable. Breaking firmware into discrete, testable modules makes development manageable and updates safer. Code optimization isn't optional — assembly-level optimization for critical loops, efficient data structures, minimal memory allocation. Every cycle counts.

And documentation: comprehensive documentation of system architecture, integration workflows, and hardware dependencies.

Conclusion

AI and machine learning are adding new dimensions to firmware development for drones (computer vision for obstacle avoidance, predictive maintenance, autonomous navigation) but these capabilities demand even more processing power and memory.

If you're developing drone systems and running into these challenges, whether it's real-time performance issues, security concerns, regulatory compliance, or making everything fit into limited hardware — we'd love to help.

FAQ

What is the difference between firmware and embedded software in drones?

Firmware is the low-level software permanently stored in read-only memory that directly controls hardware components like motors, sensors, and communication modules. Embedded software sits at a higher level, handling navigation logic, mission planning, and complex decision-making. Think of firmware as the nervous system and embedded software as the brain.

Why is firmware critical for drone flight stability?

Flight stability depends on firmware executing control algorithms hundreds or thousands of times per second with precise timing. Any delay or inconsistency in these calculations directly affects how well the drone maintains its position and orientation. Without reliable, real-time firmware, stable flight is impossible.

What are the biggest challenges in drone firmware development?

The biggest challenges include meeting real-time performance requirements with limited processing power, managing severe memory and storage constraints, implementing robust safety and fault-tolerance mechanisms, securing firmware against potential attacks, and ensuring regulatory compliance while maintaining optimal performance.

What security risks exist in drone firmware?

Key security risks include unauthorized firmware modifications, GPS spoofing attacks that provide false location data, communication hijacking where attackers intercept control signals, and exploitation of vulnerabilities in update mechanisms. Implementing secure boot processes, encrypted communications, and authenticated updates is essential.

How do developers test drone firmware before deployment?

Testing involves software-in-the-loop (SIL) simulation for initial algorithm validation, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing where firmware runs on actual processors but with simulated sensors, bench testing with real hardware in controlled environments, and finally flight testing under various conditions. Automated unit tests and continuous integration pipelines catch issues early, but real-world flight testing is irreplaceable.